Ecological economists’ view on value and prices

Inge Røpke

Socio-economic analyses such as CBA require a common unit of measurement in the form of money. When the advantages and disadvantages are put into monetary terms, things can be added and subtracted in order to reach a final result. From the point of view of mainstream economists, the fact that not all the pros and cons have a market price that can be included in the calculation is a challenge for CBA. If the construction of a motorway damages a nature reserve, there is no obvious market price of what has been lost. Therefore, the value of what has been lost has to be estimated by using different methods like those described in the first section of this theme.

Such efforts are based on the idea that market prices are an appropriate expression of what something is worth and, therefore, it is relevant to construct market prices when they are not available. Neoclassical economics can be critical of market prices as a value measure if they arise on markets that do not function optimally as they should according to the theory. On perfect markets, there must be, among other things, many buyers and sellers (i.e. not monopolies) and no so-called external costs, where production has unintended side-effects for others in the society that the producer does not pay for. However, the imperfect market is considered to be an exception, which does not seriously obstruct the use of market prices as a measure of value.

Ecological economics is more radical by arguing that market prices are not a relevant measure of value, even when markets function ‘perfectly’. As discussed in the theme on growth, ecological economics has no suggestion as to how society’s annual production of use values can be added together in order to measure the output. There is no common characteristic of use values that makes it possible. Ecological economists consider incommensurability to be a fundamental condition.

Historically, such a point of view has been unsatisfactory. According to the classical economists of the 19th century, goods are comparable through their exchange value, which is based on the amount of work that was used in their production - partly the direct work of the actual production process and partly indirect work involved in producing the raw materials, semi-manufactured materials and the machines that are gradually worn out. According to this labour theory of value, value is based on the work effort measured in time and is, thus, solely determined by conditions on the production side.

As an alternative, others have argued for the adoption of an energy value perspective, where the direct and indirect energy consumption involved in producing the goods determines their value. Due to the great importance that energy is ascribed in ecological economics, one may expect that the field would adopt such an attitude. However, this form of ‘objective’ measure of the value of a good, which is solely based on one or another kind of cost, is clearly unsatisfactory as a measure of what the good is worth to the user.

Therefore, how should we determine the value of a good from the user’s perspective? Neoclassical economists suggest that utility is reflected in the user’s willingness to pay at a given time. However, as neoclassical economists are aware, willingness to pay can not be found in the market price because some of the users would have been willing to pay more than the market price (in neoclassical theory this is referred to as the consumer surplus). In addition, willingness to pay is largely determined by ability to pay, which is very unevenly distributed. This means that the market price does not reflect the high value some goods may have for those who can not pay. Finally, willingness to pay is an expression of individual preferences rather than collective priorities, which may be thought to show more consideration for the common good and ethical principles. Neither willingness to pay nor market prices can be considered societally relevant indicators of what goods are worth.

In practice, market prices emerge as a result of interaction between supply and demand, which again reflect many different factors: uneven income and wealth distribution nationally and globally, physical and social structures that are based on decades where the environmental impacts of production have not been priced, power structures and cultural ideas that influence the relative wages for different types of work, etc. In other words, market prices are historically constructed and in many ways are influenced by inequality in the past and present. When we want to make societal priorities regarding the environment as well as in other areas, market prices can not be considered ‘objective’ input to the decision-making process. Furthermore, the validity of attempting to find the ‘correct’ prices for goods that do not have a market price is highly questionable. What goods are worth to us and what it has cost to produce them has no objective answer, but rather a series of different answers which depend on your particular point of view and priorities.

At the same time, the fact that we in society have to prioritise, set environmental goals and decide which methods to use to achieve the goals is unavoidable. When incommensurability is a fundamental condition, prioritisation must necessarily be a political process. Therefore, ecological economists often prefer prioritisation methods that illuminate the political decisions rather than hide them behind calculations that are supposed to be ‘objective’. Consequently, research is conducted on some of the alternatives to CBA which were discussed above. This includes some of the problems which are associated with the deliberative methods, such as how to ensure representativeness and counteract the inequality that is associated with different groups’ qualifications and background for participating in the debates.

In practice, ecological economists often find themselves in a position where it is necessary to become involved in a battleground, in which a CBA is designed, in order to promote a specific development in a particular area. However, as described in the section on the view on nature and ethics, this can be problematic as it paves the way for a logic that will always be able to suppress considerations for nature and ethics.

Alternatives to cost-benefit analysis - an example

Emil Urhammer

Decision support tools

When discussing major construction projects, such as motorways, wind farms or bicycle infrastructure, it has gradually become routine to include socio-economic analyses in the form of cost-benefit analysis (CBA). Therefore, CBA has become an important tool of persuasion when it comes to making decisions about major public projects and investments. However, CBA is only one of several tools that can be used to guide what is a complicated and difficult decision. In the following, we present some different decision support tools which are based on a current example.

The Hærvej motorway

At the moment, there is a discussion about whether a new highway called the ‘Hærvej motorway’ should be built in Jutland. The incumbent government, several mayors in Jutland and business representatives are advocates of the project, while local activists, the Danish Society for Nature Conservation and the environmental organisation, NOAH, oppose it. The arguments on the yes-side focus on creating economic growth, reducing transport times and fighting congestion, while the arguments on the no-side focus on preserving the beautiful landscape, and assert that highways do not fight long-term congestion and that car-use is harmful to health, has negative consequences for the climate and is noisy.

CBA

If you want to use a CBA to determine whether the motorway should be built, all the benefits need to be added together to give a total from which all the disadvantages have to be deducted to see if the end result is in favour of the motorway or against it. On the positive side is reduced transport time and less congestion, while degraded nature values and noise pollution are on the negative side. However, one of the problems with this approach is that all the advantages and disadvantages must be assigned a monetary value in order to be included in the calculation. In practice, this means that many important elements are omitted from the calculation or are not assigned a reasonable value. Thus, there is a risk that the analysis will be in favour of the interests that are best at ‘manipulating’ the calculation to their benefit. Partly in order to overcome this problem, various alternatives to CBA have been developed over time. In the following, we present some of these.

Multi-Criteria Analysis

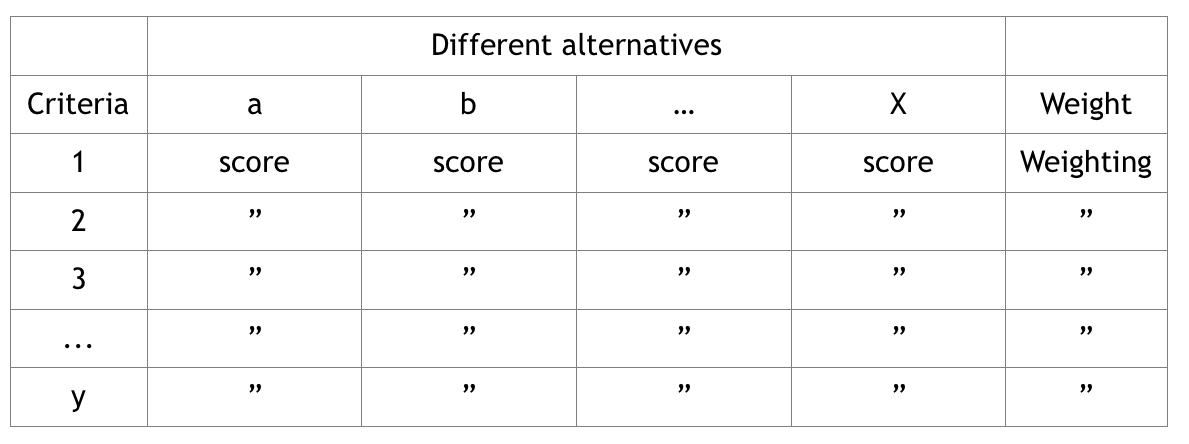

As the name suggests, multi-criteria analysis involves approaching a particular decision on the basis of several criteria. It should be stressed that these criteria are also numerical, but it is important to note that these figures do not have to be in DKK. Thus, if we take the example of the Hærvejs motorway, figures in the form of the construction cost (in DKK), reduction in transport time (in hours), increase in CO2 emissions (in tonnes), noise increase (in decibels) and reduction of area (in square kilometres) may be included. This provides a more nuanced numerical analysis that does not reduce everything to monetary value. In addition, an attempt is made to involve alternative options. In the case of the Hærvej motorway, the alternatives could be the development of public transport or the expansion of existing motorways.

As well as the numerical calculations, multi-criteria analysis also involves some consistent roles in the decision-making process. For example, decision makers (e.g. a town council or government), analysts (e.g. experts in nature or traffic), stakeholders (e.g. landowners and companies) and citizens (the wider population with an interest in the problem). When you conduct the analysis, you can let the various stakeholders fill out a form where they prioritise the alternatives and indicate how they weigh the different figures in the analysis. An environmentalist would probably put more weight on figures that emphasise natural values, while a business owner would probably put more weight on transport times and opportunities for lower transport costs.

Multi-criteria table. The table shows the general layout of a multi-criteria analysis, where alternative decision-making options are presented next to each other, and different criteria are given a specific weighted score. The table is a reproduction of a similar table in Arild Vatn’s book ‘Institutions and the Environment’.

If you wanted to conduct a multi-criteria analysis of the Hærvejs motorway, you would have to put a figure on all the different elements that are part of the problem: how much will it cost to build the motorway? By how much would transport time be reduced? How much valuable nature would we lose? By how much would noise increase? By how much would CO2 emissions increase? And how would the various stakeholders weight these inputs? Ultimately, one hope that the tables prepared in connection with the analysis would guide the decision maker and provide a nuanced basis for the decision.

Deliberative methods

The so-called deliberative methods focus on communication, interaction and arguments. Here it is about involving the public in discussions about a given problem and providing input to decision makers. One of the purposes of the method is, thus, to create opportunities for achieving consensus and compromise in relation to various value conflicts. If you wanted to use deliberative methods in connection with the Hærvejs motorway, you would try to involve the public by establishing: focus groups, citizen juries and consensus conferences.

The focus group involves gathering together a randomly selected group, which is led by a chairman. The problem that the group has to discuss is defined in advance, and there must be no direct stakeholders or experts in the group. The work of the group is not meant to result in a conclusion. The aim is instead to contribute input to the decision-making process. For example, in the case of the Hærvejs motorway, the route of the motorway could be known in advance, and there must not be any people who would be directly affected by the motorway or any traffic experts in the group. Based on the knowledge and opinions of the individual members, the group should discuss the pros and cons of the motorway and send their reflections to decision-makers.

A citizens’ jury, like the focus group, is also composed of randomly selected citizens, but in contrast to the focus group, there are more members, and the jury is tasked with reaching a final recommendation. In connection with the Hærvejs motorway, the recommendation could be, for example, that the motorway should not be built, and instead public transport should be extended. The idea is that the jury then convenes different stakeholders and experts who can qualify the jury’s recommendation. A citizens’ jury often lasts from three to five days, and it is preferable that the panel reaches a consensus regarding a recommendation, but if this can not be achieved, a final vote can be made.

Consensus conferences are almost the same as a citizens’ jury, but they have a stronger focus on consensus, i.e. the panel discusses and reaches a consensus rather than voting on a decision. In Denmark, the Danish Board of Technology, in particular, has held a wide range of consensus conferences over the years.

[otw_shortcode_info_box border_type="bordered" border_style="bordered"]Value-articulating institutions

When studying societal decisions, it becomes clear that certain institutions can help highlight some values while making sure that others stay in the background. In order to handle this value-forming characteristic of institutions, ecological economists, such as Arild Vatn, apply the concept of value-articulating institutions. Here institutions are understood in very broad sense as rules we follow in all kinds of different contexts: A family rule that the children have to clean up after dinner, or the procedure for setting up a cost-benefit analysis; both can thus be perceived as institutions. Both cases may be defined as value-articulating institutions. In the first example, the institution marks a family value that the children should also help with the housework, while in the latter case the institution determines which values should be taken into account when making a social decision and what price they should be assigned in the calculation. These two examples are very different, and usually the concept of value-articulating institutions is limited to different decision-making tools like those previously described in this section.

When cost-benefit analysis is used as a value-articulating institution, sometimes it is necessary to value a good that does not have a price. One of the methods used is to ask people about their willingness to pay for the good. For example, if the Hærvejs motorway were to be built through a special nature reserve, which would make the reserve less attractive, people could be asked what they would be willing to pay for an annual entrance ticket to the area, which could then be used to calculate the value of the area for people. This method means that people respond based on their own private interests, just as they would be expected to do when buying a product in a store. If, on the other hand, a deliberative method is used as a value-articulating institution, the participants are encouraged to formulate more collective values because they have to decide what would be best for society as a whole based on the different arguments they hear.

The reason why it is important to focus on value-articulating institutions is because their role as judges in terms of the question of value is often hidden. There is a tendency to think of value-articulating institutions, such as the CBA, as being objective and scientific, but they are in fact not value neutral, on the contrary, they favour some values at the expense of others when important decisions have to be made.

[/otw_shortcode_info_box]

Next: Ecological economists’ view on value and prices

Socio-economic analyses in practice

Jens Stissing Jensen

What is a socio-economic analysis?

Socio-economic analysis is a tool that is often used in connection with establishing political priorities for major societal investments. This could be, for example, investments in new roads, sewers or district heating systems. In addition, socio-economic analyses are also used to assess the impact of, for example, new taxes and levies or new energy-saving campaigns. The philosophy behind socioeconomic analysis is to weigh up the pros and cons of new investments and new types of regulation for society as a whole.

For example, a socioeconomic analysis can be used to assess the advantages and disadvantages of a new motorway. For some individuals, a new motorway will have positive effects because they will be able to get to work quicker. However, others who live close to the new road will experience negative effects in the form of increased noise and pollution. The mechanism behind a socioeconomic analysis of the new motorway would identify and weigh up all the experienced effects (also called use effects) for all the affected individuals relative to a situation in which the investment is not implemented. A key challenge in socioeconomic analysis is how to compare the different utility effects. How do we compare the negative use effects for individuals who experience increased noise, for example, against the positive use effects for the individuals who will be able to get to work quicker? In order to be able to compare such effects, they must each be assigned a price in DKK. For example, the negative use effect of increased noise can be priced by examining how much the market price of property exposed to noise falls. Another method is to ask the affected individuals how much they would be willing to pay to avoid the noise. A price for the positive use effects for individuals who will be able to get to work quicker can be estimated by calculating a price for their time (for example, 85 DKK/hour). By adding the time saved for all users of the new road together and multiplying the total by 85 DKK, the total use effect can now be calculated. Once all the positive and negative effects of the investment have been identified and converted into DKK, the overall social effect can be calculated by subtracting the negative effects from the positive.

An advantage of socio-economic calculations is that they make it possible to investigate where society gets most value for money. For example, socioeconomic calculations can be used to calculate whether the societal benefit of a new motorway on Zealand is greater or less than the societal benefit of investing in a new light railway in Aarhus. Socioeconomic analyses can also be used to identify the most effective method of solving specific problems. For example, socioeconomic analyses have been used to assess which methods are most effective at reducing Denmark’s greenhouse gas emissions.

It is important to note that socio-economic analyses are fundamentally different from, for example, government budget analyses or business analyses. Such analyses calculate the effects of new investments for a single actor and only include the effects to which can be attributed economic value on a market. In contrast, socioeconomic analyses look at the effects for society as a whole, including both the effects that can be attributed economic value on markets and those that can not, e.g. noise and air pollution.

From good relationships to good analyses

The widespread use of socioeconomic analyses in Denmark only really began to gain momentum in the mid-1990s, when its use was promoted, in particular, by the Ministry of Finance, which at that time had developed into a strong and dominant ministry. While in the 1980s, the Ministry of Finance was primarily busy making sure that public consumption was more or less in balance with government revenue, in the 1990s, the ministry began to formulate a more active agenda for its work. The Ministry of Finance no longer wanted to simply ensure that budgets were met, but also that resources were used and distributed optimally. From the perspective of the Ministry of Finance, one of the key problems was that the allocation of resources largely depended on personal relationships. For example, if a ministry had a charismatic minister or a minister with good connections with the Prime Minister, there was a high probability that the ministry would be successful in securing funding for its initiatives. From the perspective of the Ministry of Finance, there was a high risk that this allocation mechanism did not lead to the most optimal use of state resources. Therefore, the Ministry of Finance began to argue that the allocation of resources should be based on the ‘best analyses’ rather than the best personal relationships. However, analyses were not much use if their results were not comparable within an individual policy area as well as across different policy areas. Therefore, the Ministry of Finance began to promote socio-economic analyses as a common analytical ‘language’ across the entire state administration. The ministry also began to develop standardised methods to ensure the comparability of analyses across different policy areas.

Thus, the capacity of the various ministries to attract resources for their initiatives became less dependent on charismatic ministers with good connections to the Prime Minister and more dependent on their ability to demonstrate socio-economic value creation through socio-economic analyses.

Socio-economic analysis as a political battleground

In principle, socioeconomic analyses should produce a clear calculation of the effects of a particular investment or new type of regulation. In practice, however, socioeconomic analyzes always involve a large number of assumptions about the effects that are to be included and how they should be priced. These methodological assumptions have evolved into a central political battleground because they have a major influence on the outcome of the analyses.

One of the decisive methodical assumptions is the so-called discount rate. The discount rate is used to address the phenomenon of future effects being estimated to have a lower value than effects that occur here and now. Therefore, it is necessary to discount future utility effects so that they reflect their so-called present value. For this purpose, a certain discount rate is applied. For example, a discount rate of 4 per cent means that a utility effect with a value of 104 DKK, which occurs in a year, has a present value of 100 DKK. In practice, the discount rate is of decisive importance when calculating the socio-economic value of long-term investments. A high discount rate means that future utility effects will have a very low present value, while a low discount rate means that any future utility effects will have a higher present value. In Denmark, the Ministry of Finance decides the discount rate and it has often been accused of using a very high discount rate. In recent years, the Ministry has repeatedly reduced the discount rate. This means that long-term investments are calculated to have higher socio-economic value.

Another methodical battleground concerns how concrete effects should be valued. For example, in relation to valuing air pollution, one of the key discussions has been about the value of lost years of life. As individuals who are exposed to air pollution statistically die earlier than otherwise, a higher value of lost lives leads to higher socio-economic costs of air pollution, and thus higher socio-economic valuation of initiatives that reduce air pollution.

Finally, defining which effects should be included in socio-economic analyses plays a crucial role. Such delimitations are necessary as it is impossible in practice to identify and calculate all the effects of new investments or regulations.

Socioeconomic analyses of investments in cycling infrastructure are an example of how the definition of the effects can be crucial. Traditionally, socio-economic analysis in the field of transport has only focused on adverse health effects related to accidents and air pollution. When the municipality of Copenhagen developed a analytical method for cycling some years ago, they also decided to incorporate the positive health effects of physically active forms of transport. The municipality succeeded in persuading the Ministry of Transport to include these effects in their methodological manuals. Health production has since become the decisive socio-economic argument for bicycle investments as the health production derived from a single kilometre amounts to no less than 7 DKK.

Another example of how defining the effects can play a crucial role is illustrated by discussions about the inclusion of so-called broader socio-economic effects, which refer to effects that have no immediate connection to the actual investment or regulation being investigated, but which can nevertheless be classified as indirect effects. An example of broader effects is so-called tax distortion effects, which were introduced by the Ministry of Finance as a mandatory element in socioeconomic analyses in 1999. Tax distortion effects refer to the assertion that investments that are financed through taxes may have specific negative effects. This is because, for example, taxes are assumed to have negative effects on motivation to work. Therefore, higher taxes are assumed to encourage workers to reduce working hours and increase leisure time because the gain from work is reduced. Therefore, tax-funded investments are assumed to lead to lower labour supply. Based on this reasoning, the Ministry of Finance has introduced a tax distortion loss, which means that each tax-funded crown which is used for a given investment must be calculated to have a socio-economic cost of 1.2 DKK.

In response to the Ministry of Finance’s introduction of the tax distortion loss, the Ministry of Transport has, for example, attempted to introduce positive broader effects of transport investments. The Ministry argues that transport time and transport costs constitute a distortion effect on the labour market. According to the Ministry, investments that reduce transport time will thus increase labour supply as the gain from working will increase. Similarly, the Ministry argues that markets for goods and services are optimised when transport costs are reduced through investments in new infrastructure.

What the above discussion illustrates is that socio-economic analysis is not an objective tool, which merely produces neutral assessments of the effects of new investments or regulations. Socio-economic analysis is rather a complex method of calculation, where many elements need to be set and adjusted. Thus, socio-economic analysis is also a political tool because the way in which the method is set up will always suit specific interests and agendas better than others.

Next: Alternatives to cost-benefit analysis – an example

Introduction: Political decisions

While in the themes on driving forces and distribution the focus is mostly on conflicts over distribution in relation to the environment in a very broad perspective, in this theme, we examine the conflicts and dilemmas that arise in relation to environmental challenges in a narrower and more local perspective. When the political system has to deal with environmental problems, it gives rise to many dilemmas, where different interests have to be weighed against each other. In a democracy, it is not possible to exercise brute force, which means the political battleground for the environment and many other causes is characterised by arguments and methods that make these arguments convincing. If you want to promote a special interest, it is particularly effective if you can make it appear to be in the interest of society as a whole. One of these battlegrounds is focused on the design of socio-economic analyses.

The next section discusses how socio-economic analyses are applied in practice and some of the controversies that are specifically associated with the use of cost-benefit analysis (CBA). Thereafter, some alternative methods are presented that may be used to support policy decisions, while in the last paragraph, some more fundamental considerations about value and prices are discussed.

Next: Socio-economic analyses in practice