Environmental ethics

Emil Urhammer

In this section, we introduce some important concepts in environmental ethics. These concepts function as tools for discussing various environmental dilemmas and conflicts.

Anthropocentrism and ecocentrism

The problems in this theme about the view on nature and ethics can also be considered with the help of the concepts anthropocentrism and ecocentrism. The word anthropocentrism is a combination of the ancient Greek word anthropos (human) and the Latin word centrum and refers to the view that the human species is the centre of the world and is above other species, and that the interests of humanity override concern for other species. Several environmentalists have used the concept to point out how concern for humanity’s survival and well-being is now on a collision course with the life-sustaining systems on Earth to the detriment of other species and humanity itself.

In contrast to anthropocentrism, ecocentrism, like ecophilosophy, expresses the belief that humankind is just one of many equal pieces in the planet’s whole ecosystem. In this way, ecocentrism highlights humans as being part of nature and not a species separate from it. According to an ecocentric world view, other species are equal to humans, and consideration of other species is just as important as consideration of humans. In relation to this, it should be mentioned that the environmental ethicist, Finn Arler, has put forward the argument that ecocentrism is also anthropocentric because it is not possible for humans to look beyond the horizon of their species. We humans will always put ourselves in the centre of our view of the surrounding world. This manifests itself in dilemmas, whereby, even though one wants the best for all species, one ends up prioritising human considerations. Rasmus Ejrnæs gives a humorous example of such a dilemma in connection with ‘pests’ such as Spanish slugs. On the one hand, one may argue that Spanish slugs have just as much right to live as any other species, but it may be necessary to kill them when they eat one’s home-grown salad.

Intrinsic and instrumental value

In environmental ethics, the concepts inherent and instrumental are often used to talk about the value of different natural goods. If you believe that a rare butterfly or a particular plant has value in itself, i.e. value regardless of whether humans know of its existence or like it - one can say that the butterfly or plant has intrinsic value. If, on the other hand, you think that the rare butterfly or plant only has value because people derive pleasure from it or can use it for something, then the butterfly or the plant has instrumental value. In the latter case, the butterfly’s beautiful colours or the plant’s tasty berries could be examples of instrumental values.

When discussing different social priorities, such value perceptions may also play a role. To put it simply, one can say that there is often a tendency to prioritise natural goods higher when they have instrumental value, i.e. value for humans. An unspoilt nature area will, in the eyes of many, have greater value if people have access to it and can use it for recreational purposes than if it just exists somewhere untouched without being of direct benefit to humans. However, the unspoilt area may be the habitat for many species and is, therefore, important for preserving biodiversity.

In order to preserve biodiversity, it may be necessary to emphasise the inherent value of all species. This approach emphasises that a boring gray beetle has just as much right to live as a colourful butterfly or a pet. Rasmus Ejrnæs has argued that humanity does not need great biodiversity to survive on Earth, which means that the conservation of biodiversity requires other moral arguments such as the fact that all living beings have inherent value and thus the right to live regardless of whether we humans have a use for them or not.

If you think about it a little more, you will discover that inherent and instrumental value are not separate or mutually exclusive. It is, thus, possible to consider something as having both inherent and instrumental value at the same time. For example, you might enjoy a butterfly’s colours, while at the same time thinking that the butterfly has value in itself, regardless of whether you enjoy looking at its colours or not.

The idea of intrinsic and instrumental value can also be linked to the more overall world views of anthropocentrism and ecocentrism in the sense that instrumental value can be understood as an anthropocentric value perspective, whereas intrinsic value is well-aligned with the ecocentrist perspective. However, there is no need to make a sharp distinction between the two and say that anthropocentrism only encompasses instrumental values and vice versa. Instrumental value can also be considered ecocentric, while intrinsic value can also be considered anthropocentric. For example, in the first case, a flower may have instrumental value for a bee (instead of a human being), so you could say that only humans are able to understand the concept of intrinsic value and, therefore, this whole idea is anthropocentric.

Ecosystem services

The idea of inherent and instrumental value is also related to our perception of ecosystems and their conservation. If you have an instrumental view of ecosystems, you will interpret an ecosystem as something that provides a service to people. Thus, from a human point of view, it is the function of the ecosystem that gives it value. For example, a forest is an ecosystem that supplies different services to humans. It can clean rainwater on its way down to the groundwater, thereby delivering clean drinking water. It can also deliver timber, and it can be a place where you can find peace or exercise.

If you have such a perspective on the forest, it becomes natural to want to attribute a monetary value on the services it provides. Thus, some believe that the ability of the forest to deliver clean drinking water has a monetary value that can be referred to when arguing that the forest should be maintained. On the other hand, others believe that this is a dangerous road to take as it means that other actions which have a higher monetary value can trump the goal of preserving different ecosystems. If we take a species rich and diverse forest as an example and assume that the ability of the forest ecosystem to clean rainwater is worth 5 million DKK a year. If I can demonstrate that felling all the trees and establishing an industrial plantation with only one species of tree would provide 7 million DKK a year, I would have a strong argument for felling the forest. Therefore, to avoid such a slippery slope, several environmentalists believe that we should instead emphasise the unique values and beauty of the forest without trying to put a monetary value on its services. The forest has inherent value and a right to life that can not be valued in money.

Incommensurability

One of the problems in the discussion of value is the question of value comparability or rather the lack of the same. For example, does it make sense to compare the value of an endangered animal species with the value of a large construction project that is threatening the habitat of the species? And is it at all possible, in such cases, to objectively determine what is most valuable and, therefore, should be given the highest priority?

As mentioned in the previous paragraph, some attempt to solve such problems by calculating monetary value as they believe that market prices can decide what is most valuable and should be given the highest priority. According to this logic, the market price is regarded as a credible expression of the value of something, which means that market prices enable comparison between very different things. However, among ecological economists, there is widespread scepticism about this view, and instead they propose that we must accept incomparability and that there is no single measure by which we can compare all values. Instead, democratic methods should be developed to discuss value, priorities and decisions from many different angles instead of blindly letting market prices dictate.

Nature - in the service of humans

Susse Georg

There are many ways of defining nature, but the view of nature as a resource has gradually become widespread. Here nature is regarded as a supplier of raw materials or resources, including the energy we use to maintain society. Among the essential raw materials are, for example, pure drinking water, agricultural land, rare earth metals and different types of energy carriers such as wood, coal and oil. Some of these materials are renewable, i.e. they can be restored (within the foreseeable future), while others can not and are considered non-renewable. Wood is considered renewable because a forest can grow again. On the other hand, coal, gas and oil - the fossil fuels, which are formed by organic matter (plants and algae) having been under pressure under the ground for many millions of years, are not considered renewable raw materials.

Humans use incredible amounts of raw materials. For this reason, there is great interest in determining the size of the stock of raw materials and how nature’s material flows function. In view of the increasing human population, determining whether there are enough resources to maintain our growing consumption so that future generations will also have an opportunity to use natural resources has become important. However, there is no simple answer to this question. Some have stressed that there are ‘limits to growth’, while others claim that as a result of technological development we will be able to find alternatives and, thereby, reduce or completely eliminate our dependence on certain limited raw materials. Although this may, of course, be possible in many cases, there seem to be some raw materials that can not be replaced by others. This includes, for example, phosphorous, which plays a crucial role in plant photosynthesis and in food production.

One can also apply a so-called process view of nature, where material and energy flows and their interaction with living organisms are central. This interaction between living organisms and their physical environment - between the biotic and the abiotic – takes place in ecosystems whose development is determined by the mutual influence and dependency of organisms and their environment. Thus, biological, physical and chemical processes form part of a wide range of mutually influencing cycles.

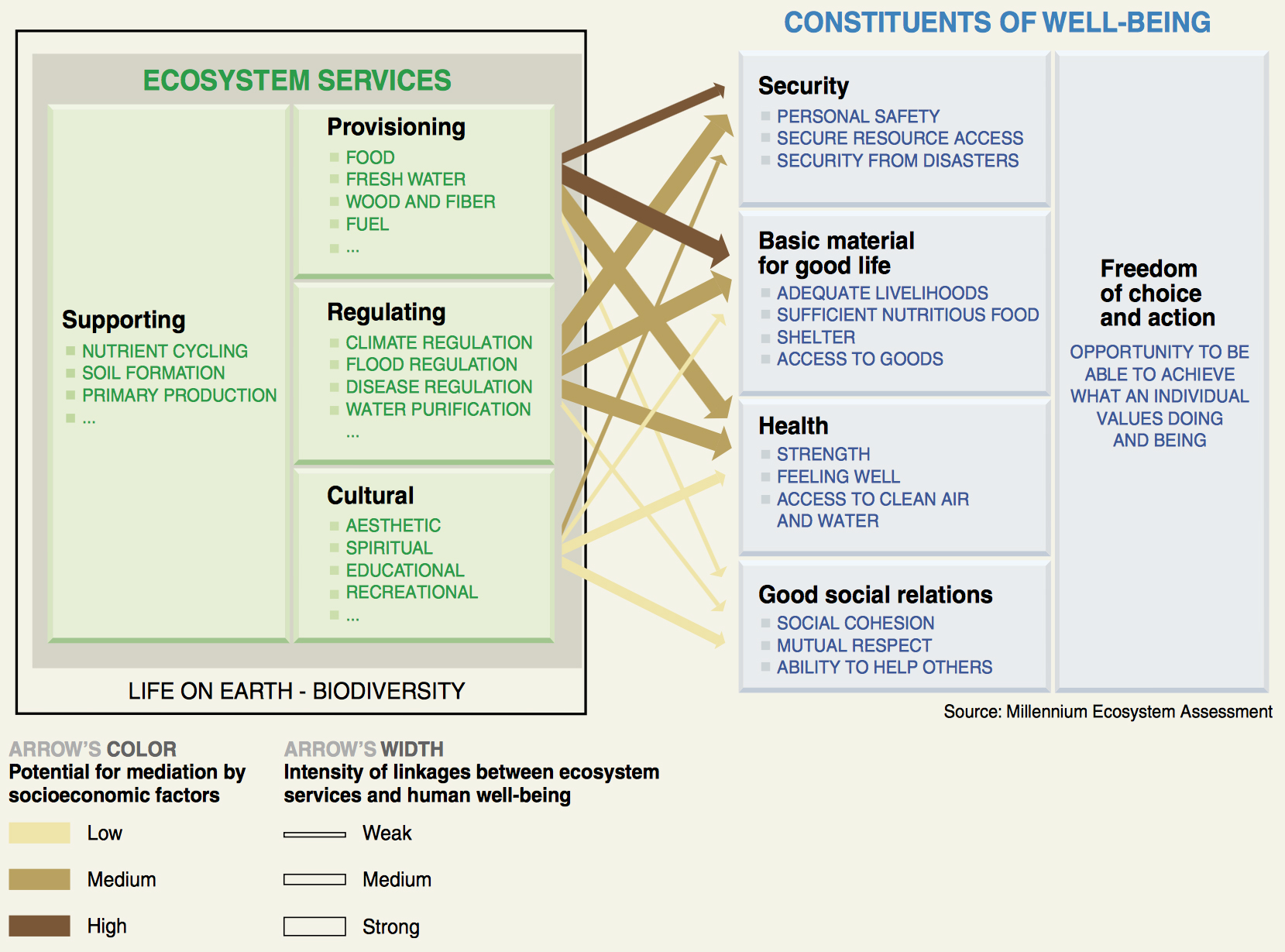

From a human perspective, the results of these processes are often termed ecosystem services, and they are vital to the maintenance of life. A distinction is made between the following four types of ecosystem services:

- Provisioning services such as the provision of food and wood for furniture production and construction. These services are not only based on natural resources and material/energy flows, but also depend on the use of human labour, machinery, etc.

- Regulatory services which are linked to the capacity of ecosystems to, for example, convert (and retain) nutrients in the soil or water and in this way may affect soil and water quality. The pollination of plants is another extremely important regulatory service as it affects food production. If plants were not pollinated, production would decrease. In this connection, the decline in the number of bees has attracted much attention.

- Cultural services are the experiences people can get from ecosystems, for example, in connection with recreational activities such as hiking in the woods, or picking flowers and berries. Landscapes can also provide such services by containing things that are considered valuable and worthy of conservation, for example, geological formations, such as cliffs, or different types of cultural heritage such as burial mounds.

- Supporting services are those that support the provision of the other services. Examples include photosynthesis, nutrient cycles and different soil conditions.

Therefore, ecosystem services are crucial to our well-being - our mutual relationships, health, quality of life and safety. For this reason, these services must be protected or managed in such a way that they are not destroyed by pollution or overuse. For example, chemicals can leach into the groundwater and destroy our drinking water, agricultural soils can be exhausted so that it is not possible to maintain agricultural production, and the habitat of pollinating insects can disappear so that the population of such insects decreases or completely disappears.

However, there are many indications that our use of ecosystem services is out of control. According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Report of 2005, during the last 50 years, ecosystems have changed so much that they are either overloaded or are about to be destroyed. In other words, humanity is well on the way to undermining society’s opportunities for future development as there is a risk of rapid irreversible changes to ecosystems which may have serious consequences for our well-being. Against this background, many have begun to assert that there are limits to what the planet’s ecosystems can cope with - the so-called planetary boundaries (see the infobox on ‘planetary boundaries’ in theme 3, ‘Growth and the environment’).

The two perspectives on human relationship with nature discussed above provide two different descriptions of the challenges we face. From a resource perspective, it is important to determine how many raw materials we have left, where they are and how accessible they are. What becomes worrying in this connection is whether we will run out of certain raw materials, and if so when, and whether it will be possible to find suitable alternatives and if not, what will be the social, political and economic consequences. In the process perspective, the focus is not on individual raw materials or resources, but rather the dynamic interaction between (biological) organisms and their surroundings and between different ecosystems. Thus, it represents a systemic perspective where the concern is not only that societal development will lead to resource scarcity, but also changes in the dynamics of ecosystems and, thus, their resilience. Limits to growth are also applicable here; limits connected to the destruction of the fragile balance of ecosystems, which, if pushed too far or destroyed, will undermine conditions for life. The transition of society in a more sustainable direction, thus, requires caution in terms of how we deal with nature regarding both our use of raw materials and ecosystem services.

Nature and ecophilosophy

Emil Urhammer

At first glance, the word nature may not seem very complicated. Nature; it is the forests, mountains, rivers, animals and plants. However, if you think about it more deeply, it may not be so easy to define nature. Is a corn field that has been grown by humans, or a forest that has been planted by humans, or a stream whose meanders have been restored by humans, nature? There is probably no unequivocal answer to this question. Some would say yes because they think everything is nature. According to this understanding, human culture, cities, and technology are also considered to be part of nature. Such a view is also called deep ecology or ecophilosophy. According to the late Norwegian ecophilosopher, Arne Næss, human beings are an integral part of nature, and the moral basis for humanity is to achieve a situation where people are living in ecological balance with their surroundings. Næss believed that humans are the first species on Earth who are able to consciously relate to their own role in nature. For example, humans can assess whether the total number of people is too large for us to live in balance with the rest of life on Earth. This imposes a moral responsibility on humanity, which other species do not have. However, given the current situation, one may ask how worthy we are of this obligation.

In addition, some assert that human society and nature have become separated. For example, the biologist, Rasmus Ejrnæs, says: ‘The separation between nature and humans now demands that we either file for a permanent divorce because living together has become too difficult, or that we prepare ourselves for peaceful coexistence and focus on biodiversity’ (in the book Natur, Tænkepauser – viden til hverdagen, Århus Universitetsforlag 2013). Ejrnæs is a biologist who works with species diversity, which is also called biodiversity. The philosophical question of whether humans are part of nature is probably not his most important consideration. He just observes that the way people are currently living is in violent conflict with most of the other species on the planet, which is why he encourages us to recognise that we need to find a way of living in peaceful coexistence if we want to preserve biodiversity. In this way, Ejrnæs’s interpretation is perhaps not so far from Næss’s dream of people living in ecological balance with their surroundings.

Population

In terms of achieving balance and peaceful coexistence between humans and other species, the question of population plays a central role. Some think that the fact that there will soon be 10-11 billion individuals on the planet is not a problem, while others believe that the current population of approximately 7 billion is already far beyond what is beneficial to both humans and other species. This discussion is extremely complicated and involves both moral and more technical aspects. If you always think ‘humans first’, the fact that we are so many may be interpreted as a sign of humanity’s strength and superiority. If you have this opinion, you may not think it is a problem that a lot of species are dying to provide space for human activities. On the other hand, if you think that all other species, in principle, also have the right to live, you will probably think that it is extremely problematic.

The more technical side of the issue is that we humans could probably learn to take up a lot less space and fewer resources if we just gave it some thought and organised ourselves differently. For example, several environmentalists believe that if we stopped eating meat, it would allow other species to thrive. The reason for this is that meat production takes up a lot of land because the animals that we eat need very large amounts of water and feed. In this way, we use a huge area of land to feed the animals we eat. If we did not eat animal products, this area would be reduced and could instead be used by other species.

Not only biological life

In the discussion of humans’ place in nature, people often talk about humans in relation to other biological life, but the question is more comprehensive than that. In principle, these considerations also concern, for example, mountains, rivers and the oceans. What is the significance of blowing up mountain peaks to find coal? Or damming rivers? Or filling the ocean with plastic waste? Among indigenous tribes, it is not uncommon to consider mountains or rivers as living things which also have rights. If you understand the world in this way, how we treat the mountains, rivers, oceans and the air is very important as they are often perceived as conscious and sacred beings. According to such a perspective, not only humans have rights as mountains and rivers are also considered to be living creatures with special rights. For example, in South America, attempts have been made to include the rights of nature in the constitution of certain countries.

[otw_shortcode_info_box border_type="bordered" border_style="bordered"]View on Nature

The philosopher, Hans Fink, has worked extensively with the concept of nature and has identified seven different widespread interpretations, which can be seen as different ways of perceiving nature. Here is a brief description of each.

- Nature as ‘unspoiled’ is the idea of nature as being that which is completely untouched by humans. Therefore, nature is that which is still in its original state; untouched by human influence. According to this perspective, a remote desert or untouched virgin forest is nature.

- Nature as 'wilderness' is the idea that nature as that which has not been cultivated by humans. This idea is connected to the difference between cultivated and non-cultivated land. According to this view, nature is: virgin forest, mountains, deserts, marshes, tundra and wilderness which is inaccessible to humans, although forests, heaths and beaches that people frequent and exploit for hunting, fishing and the gathering of wood, are also considered nature. The antithesis of nature, in this perspective, is the cultural landscape, which is the subject of human cultivation and planning.

- Nature as 'rural' is the idea that nature encompasses everything in the countryside outside towns. In this view, it does not matter whether the land has been cultivated or is untouched. What is important is that it is not a town. The border of nature thus extends to the outskirts of the town.

- Nature as 'green' is the notion of nature as living and organic. Therefore, the dividing line between nature and culture cuts across towns and countryside and concerns the difference between organic and synthetic. In this perspective, a wooden spoon is more natural than a computer or an artificial chemical, and the city’s gardens, parks and potted plants are also considered nature, whereas concrete buildings, asphalt roads and plastic bottles are not.

- Nature as ‘physical’ is the idea of nature as that which science is concerned with. Therefore, nature is phenomena such as gravity, electromagnetism, atoms, black holes and energy. According to this view, nature is objective as opposed to subjective, social and cultural.

- Nature as ‘earthly’ is the view of nature as that which has been created by a divine being. In this perspective, nature comprises the material world we live in, which is in contrast to the heavenly or spiritual kingdom where God resides.

- Nature as ’everything’ is the idea that nature comprises everything: the world, the universe, the cosmos, etc. In this view, everything from deserts and cultivated fields to electronics and smart ideas are nature. Thus, in a way, all the other ideas are combined together into one: Everything is nature.

Listen to Hans Fink talking about the seven view of nature here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MspVir4Qr04&feature=youtu.be

[/otw_shortcode_info_box]

Next: Nature – in the service of humans

Introduction: View on nature and ethics

The term, nature, plays an important role in the understanding of sustainability. The way we perceive nature influences how we treat the different species with which we share the planet. If you think the ocean is a pantry for humans, you will probably be less inclined to think that life in the ocean is not necessarily just for human survival and satisfaction. If you primarily think of the pleasure you derive from eating meat, it is less likely that you will consider the fact that meat production raises ethical questions and has consequences for nature around us. Meat production often entails animals being caged in with very little space, tied up and exposed to pain.

Indeed, agriculture as a whole means that areas with great species diversity are continually being transformed into so-called monocultures, where the diversity has disappeared and only a few crops grow. This certainly meets human needs, but it does not benefit many other species on Earth. Through time, ethical problems of this type have been the subject of philosophical reflections about humans’ relationships with nature. Such reflections concern the way nature is viewed and ethics; the latter meaning philosophical considerations of a moral type. In this theme, we provide a brief overview of some important topics in this field.

Next: Nature and ecophilosophy